Overview

Disclaimer: This note is mostly inspired by the Lightbend: How Akka Works series

While studying for my AWS certification, I explored the concept of "At-least-once delivery" in SQS. Delving deeper into this topic, I sought to understand the significance of various messaging patterns in distributed systems. In contemporary architecture, systems consist of discrete, well-defined components with message queues facilitating communication and coordination. These principles extend to messaging in other distributed systems, including microservices.

Object and Actor Messaging Basics

In object-oriented programming languages, objects respond to method calls. Object method calls are a form of sending messages to an object. The object philosophy is that "everything" is an object. In Akka, with its implementation of the actor model, the philosophy is that "everything" is an actor. (The term "everything" is used loosely here. Of course, not everything is an object or an actor; the idea is that these are the dominant players in these software systems.) Both objects and actors react to messages. However, things quickly diverge from there.

One of the most fundamental differences between the object philosophy and the actor model philosophy is the act of invoking an object method is a synchronous operation while the act of sending a message to an actor is an asynchronous operation.

When a client invokes an object method, the method caller waits for the method to complete and when the method is finished the caller resumes execution. On the other hand, when a message is sent to an actor the message sender is not suspended. The message sender sends a message, and it continues running. In fact, sending a message to an actor is handled by the actor system via method calls to what is referred to as an actor reference. Actor references represent a transparent reference to an actor that may be located somewhere within an actor system, and the actor system may actually be distributed across multiple JVMs that reside on multiple network nodes.

Threading in actor model

Objects typically process within a single thread of execution. Of course, using multiple threads is an option, but the most common case is that a single thread handles the flow of objects invoking methods of other objects.

With actors, the sender of a message and the receiving actor are separated. That is the message sender does not directly interact with the message receiver. As a result, the message sender and the message receiver are running on separate threads. Also, the message sender and the message receiver may be running in separate processes, and those processes may be running on separate network nodes. This separation of the message sender and message receiver also applies to message passing between networked services, such as microservices.

Key notes

The key point is that while object methods are directly invoked synchronously by the caller messages sent to actors are sent asynchronously via the actor system.

Creating an actor in software is very much like creating an object. Each actor is written as a class with methods. The big difference is that the only way to communicate with an actor is by asynchronously sending it a message via the actor system. Only the actor system itself creates actor instances and directly invokes an actor’s methods. No user code directly invokes any actor methods.

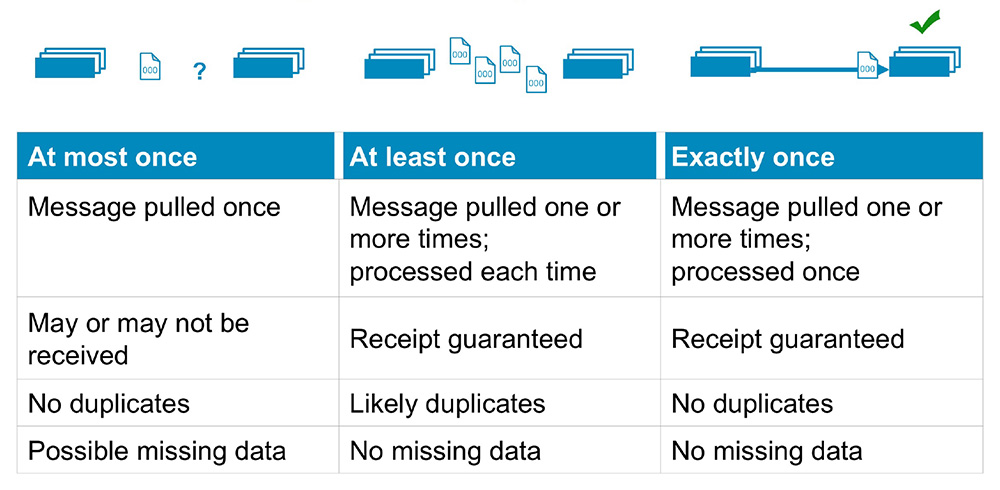

Types of messaging semantics

Explain In Plain English

At-most-once is the cheapest but highest performance, least implementation overhead—because it can be done in a fire-and-forget fashion without keeping state at the sending end or in the transport mechanism.

At-least-once requires retries to counter transport losses, which means keeping state at the sending end and having an acknowledgement mechanism at the receiving end.

Exactly-once is most expensive and has consequently worst performance because in addition to the second it requires state to be kept at the receiving end in order to filter out duplicate deliveries

Explain In Jargon

Before we dive deeper into each delivery, let's review the main types of messaging semantics. When a system is fully operational and working as intended, exactly-once delivery is the behaviour you generally expect. However, we must also consider how faults in the pub/sub system or, indeed, clients affect this behaviour.

While most components fail independently in a distributed pub/sub system, without directly impacting other components, the overall quality of service can be affected. Depending on how the system behaves when failures do occur, you get several different types of messaging semantics:

- At-most-once semantics. The easiest type of semantics to achieve, from an engineering complexity perspective, since it can be done in a fire-and-forget way. There's rarely any need for the components of the system to be stateful. While it's the easiest to achieve, at-most-once is also the least desirable type of messaging semantics. It provides no absolute message delivery guarantees since each message is delivered once (best case scenario) or not at all.

- At-least-once semantics. This is an improvement on at-most-once semantics. There might be multiple attempts at delivering a message, so at least one attempt is successful. In other words, there's a chance messages may be duplicated, but they can't be lost. While not ideal as a system-wide characteristic, at-least-once semantics are good enough for use cases where duplication of data is of little concern, or scenarios where deduplication is possible on the consumer side.

- Exactly-once semantics. The ultimate message delivery guarantee and the optimal choice in terms of data integrity. As its name suggests, exactly-once semantics means that each message is delivered precisely once. The message can neither be lost nor delivered twice (or more times). Exactly-once is by far the most dependable message delivery guarantee. It's also the hardest to achieve.

What most distributed pub/sub systems can genuinely guarantee is mostly-once delivery. This means that when the system is functioning as intended, messages are delivered exactly once. However, when failures are involved, there's always a chance some messages will be delivered either at-most-once or at-least-once.

Source:

Source: