Exactly Once

Disclaimer: This note is mostly inspired by the Lightbend: How Akka Works series

TL;DR - Exactly once is the most difficult delivery semantic to implement. It is friendly to users, but it has a high cost for the system’s performance and complexity.

Overview

As we just briefly discussed, with the at-least-once messaging approach, the best we can do is implement processes that may result in the delivery of some messages more than once.

Conceptually an exactly-once message approach is much more desirable. But, as the saying goes, “you can’t always get what you want.”

For now, consider that implementing an exactly-once messaging solution is on the same level as creating a vehicle that can travel faster than the speed of light. There are ways to get close, that is to deliver messages essentially-once but it is impossible to implement an exactly-once process that works. In part 3 of this series, we will look at this in more detail.

Use case

TL;DR - Financial-related use cases (payment, trading, accounting, etc.). Exactly once is especially important when duplication is not acceptable and the downstream service or third party doesn’t support idempotency.

The Two Generals Problem

An excellent demonstration of the challenges of distributed messaging is a thought experiment known as the Two Generals Problem. What is shown in this analysis is that there is no way to guarantee state consistency between two endpoints when any form of two way communication is used where message delivery failures may occur.

In this article, we have been using an order processing example where you and I are the endpoints. You handle orders, and I am responsible for order shipping. We each maintain state for each order that we are processing.

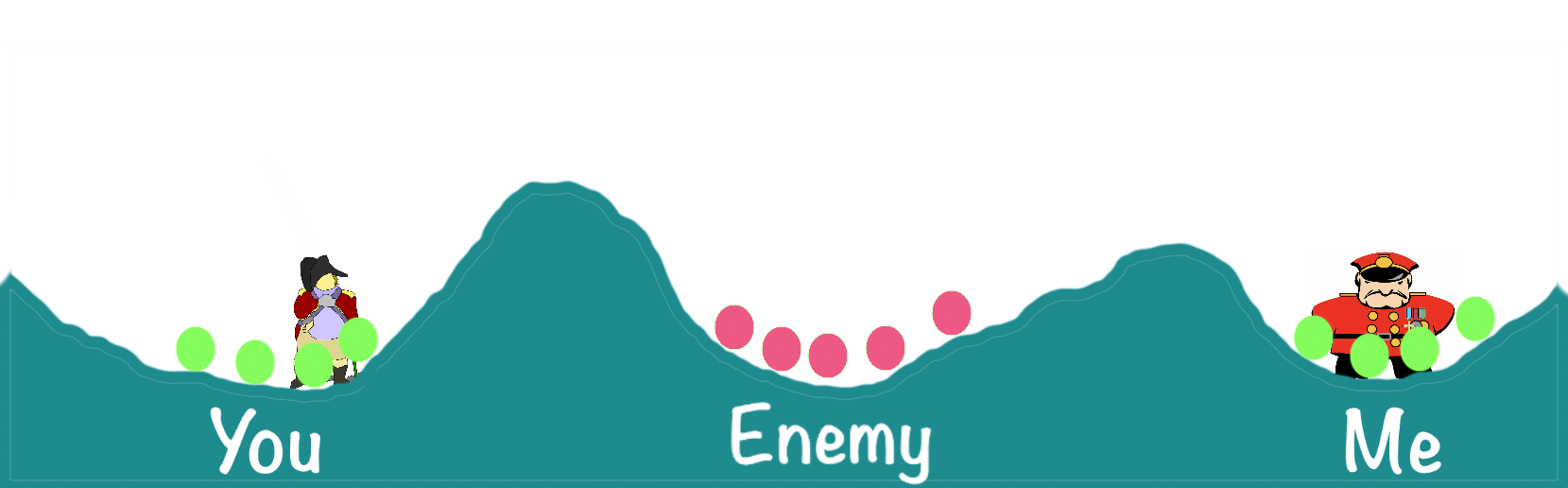

In the two generals scenario let's pretend that you and I are the two generals. We are planning on conducting a coordinated attack on a single enemy. As it happens, your army is located in one valley, the enemy is in the next valley, and my army is located in a third valley over a ridge from the enemy.

Figure 9: The Two Generals Problem

It is essential that we both attack the enemy at the same time. Jointly we have sufficient numbers of soldiers and resources required to defeat the enemy. However, if only one of our armies attacks the enemy alone, we will be defeated.

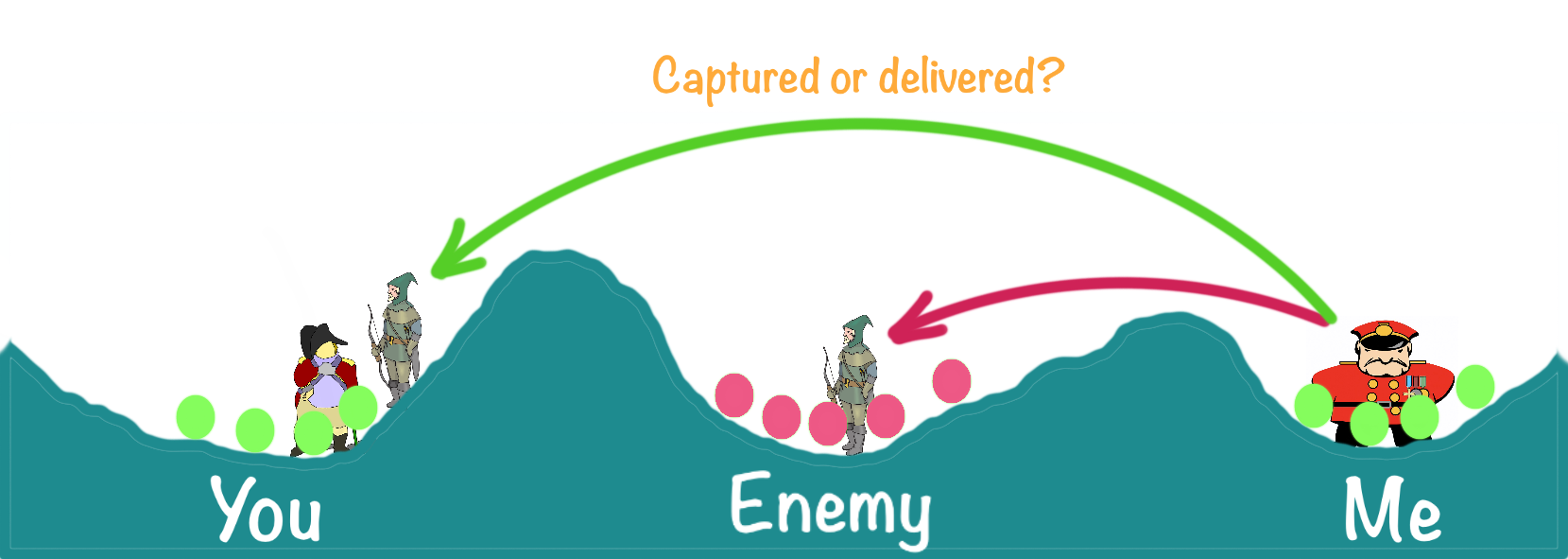

The challenge is that we have not yet agreed on a specific time to attack. We must communicate with each other via messengers to decide on when to attack. The dilemma is that the messengers must pass through enemy territory to deliver a message. Obviously, there is no guarantee that a given message will be delivered.

Say you decide that the time to attack is tomorrow at 8 am. This is essentially a state change. You are in the "let's attack at eight tomorrow morning" state. You then dispatch a messenger with this information - "we attack tomorrow at 8 am". At this point, you are waiting for my response. Without an acknowledgment from me that I agree with your plan you cannot proceed.

In our five-stage journey, you have completed the first stage, your state change decision on when to attack. Stage two involves the messenger delivering the message from you to me.

The happy path

Following the happy path first, I do receive the message. In stage three I make the state change decision to agree or not agree to your request to attack. In stage four I dispatch a messenger to deliver my reply message to you. Finally, you get my reply from me. In my reply, I've either agreed or rejected your proposed attack time, which completes stage 5. Here is the five-stage messaging journey:

- You have completed the first stage, your state change decision on when to attack

- You dispatch a messenger to deliver your message to me

- I receive the message from you and make the decision to agree with your proposal

- I dispatch a messenger to respond back to you that I have agreed to your request

- You receive my reply and now know that we both agree on the time to attack

In this happy path example, we already have a serious problem. I have no way of knowing if you received my reply. How can I attack when I am unsure if you know that I have agreed to your proposed time?

There are at least two possibilities here.

- One possibility is that you did get my reply and of course the other possibility is that the reply messenger was captured or

- worse and the message was never delivered.

In either case, I have no way of knowing what happened.

Msg being altered

Figure 10: Was the reply message delivered?

There is another more sinister possibility. The enemy captured the messenger. Then the enemy alters the message, say my reply was "I agree, we attack at 8 am". But the message is altered to "8 am tomorrow is too soon, what about the next day?" Then the messenger is forced or bribed or replaced, and the altered message is delivered to you.

The point is that many things can go wrong just with my reply to you.

What do you do when you do not get a reply from me? In this case, we have another serious dilemma. You do not know if I have received your message or not. There are at least three possibilities here.

- One is that your messenger was captured and your message was not delivered to me.

- The second possibility is that I did receive the message, but for some reason, I was unable to send a reply.

- Finally, the third possibility is that I did send a reply, but my messenger was captured.

Is there a way to fix this communication problem?

Possible solutions

One possible approach is that we require that each messenger delivers a message and then returns to the sender to verify that the message was delivered. When a message is dispatched, we wait for a finite period for the messenger to return. If the messenger does not return before the return wait time has expired, we send another messenger. We repeat this process over and over until we finally get a successful reply.

Will this modified message delivery approach work?

The short answer is no. The problem is that with this approach the message sender can know when a message was sent because the message delivery has been acknowledged. However, the message receiver does not know if a message was acknowledged.

Consider this scenario. You send a message to me, I get the message, and the messenger returns to you. The first problem is that I do not know if the messenger returned to you or not. What this means is that I can expect to see the same message from you more than once. In this scenario that is not a problem if I receive the same message multiple times.

The problem is with my response message back to you. You do not know if my messenger returned to me. You can expect that I may send my reply to you more than once because I'm using the technique of sending a messenger and waiting for a timeout period before sending another messenger. However, you cannot know if I have ever received an acknowledgement.

What this means is that we continue to have a significant communications problem. If my reply messenger does not return to me, I cannot attack as planned. At the same time, you are never sure if I will attack because you do not know if my messenger has returned to me with an acknowledgement.

Why Exactly-Once is Impossible

After walking through the Two Generals Problem, you can see that reliable message delivery is challenging. We tried to solve the problems between the two generals, the two communication endpoints, using at-least-once message delivery techniques, and we still were unable to come up with a thoroughly reliable and workable solution.

The reality is that when message producers push messages to message consumers, there are unsolvable failure scenarios that cannot be resolved. When you send/push a message to me, you have no way of knowing if I received the message or not. When I do receive your message, I have no way of knowing if you received my reply or not.

You the message sender and I the message receiver can know that there is a problem, but we cannot know in all failure conditions what happened on the other side of the wire. This is a fundamental law of the physics of distributed message communication that cannot be solved.

Often Perseverance Pays Off

It would be wonderful if there were a workable exactly-once messaging solution. Ideally, we would like to exchange messages in the same way we invoke a method or function. Just give us a reliable remote procedure call, and we will be happy. What can be so hard about that?

As is often the case, there are many ways to solve software problems. Sometimes what we need to do is step back and evaluate what we are trying to accomplish. Our order processing scenario is not like the two generals' problem. With the two generals, both parties need to coordinate their actions. In our order processing example, we merely have to perform a series of steps one after the other. Our only coordination requirement is that all of the required steps must be eventually completed.

In the case of our order and shipping scenario what we need is to exchange messages between the order and shipping services. An essential requirement is that no messages can be lost. It would be nice to have an exactly-once solution available, but it is not an absolute requirement.

Let's try push approach

Our intuition drove us towards a push approach. You send me a text message when new orders are created. I send you a text message when I've started the packing process and another message when each order is shipped.

On the at-least-once page, there are a lot of reliability problems with this push approach. The most basic problem is that sometimes messages are delivered, and sometimes messages are not delivered. Also, there is the uncertainty of not knowing what happened on the other side of the wire.

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

But we can make the push approach work - with some terms and conditions. First, you must implement a message retry approach. You keep trying to send me each message until you receive a reply from me. The Ts&Cs here is that you need to harden the retry process to the point that failures and restarts on your end do not result in your losing any messages. To do this, you will need some form of resilience on your delivered messages list, as shown above. These are all solvable problems, but it does add a level of complexity to your message sending processing.

On my end, I have to handle potentially receiving the same message more than once. As we have discussed, when using the push/retry approach this results in the receiver receiving some messages one or more times. Handling the same message multiple times is also a solvable problem. Again, this takes some additional work on my end to handle this.

So the message push/retry and message receive one or more times is doable but it is more complex than your typical HTTP REST implementation.

Maybe pull is better?

Ok, so the push messaging approach is solvable but somewhat complex when it comes to reliable messaging. What about the pull approach? The pull approach is slightly counter-intuitive, but it is typically less complicated to implement. Both the push and pull approaches were covered in detail in at-least-once of this series so please refer to that document for more details.

The push and pull approaches provide ways for implementing at-least-once delivery while the commonly used synchronous HTTP REST approach without retry offers at-most-once delivery, as discussed in at-most-once.

What about exactly-once delivery? As already stated an end-to-end general purpose exactly-once message delivery process is physically impossible to implement. However, it is possible to achieve what appears to be exactly-once messaging with techniques that are referred to as essentially-once.

Essentially-Once Messaging

The essentially-once message approach is a matter of perspective. On the receiving end what can be done is that the message receiver does not see duplicate messages, which effectively simulates exactly-once message delivery from, again only from the perspective of the message receiver. However, in between the message sender and the message receiver, we are going to have to implement some "magic" to make this happen.

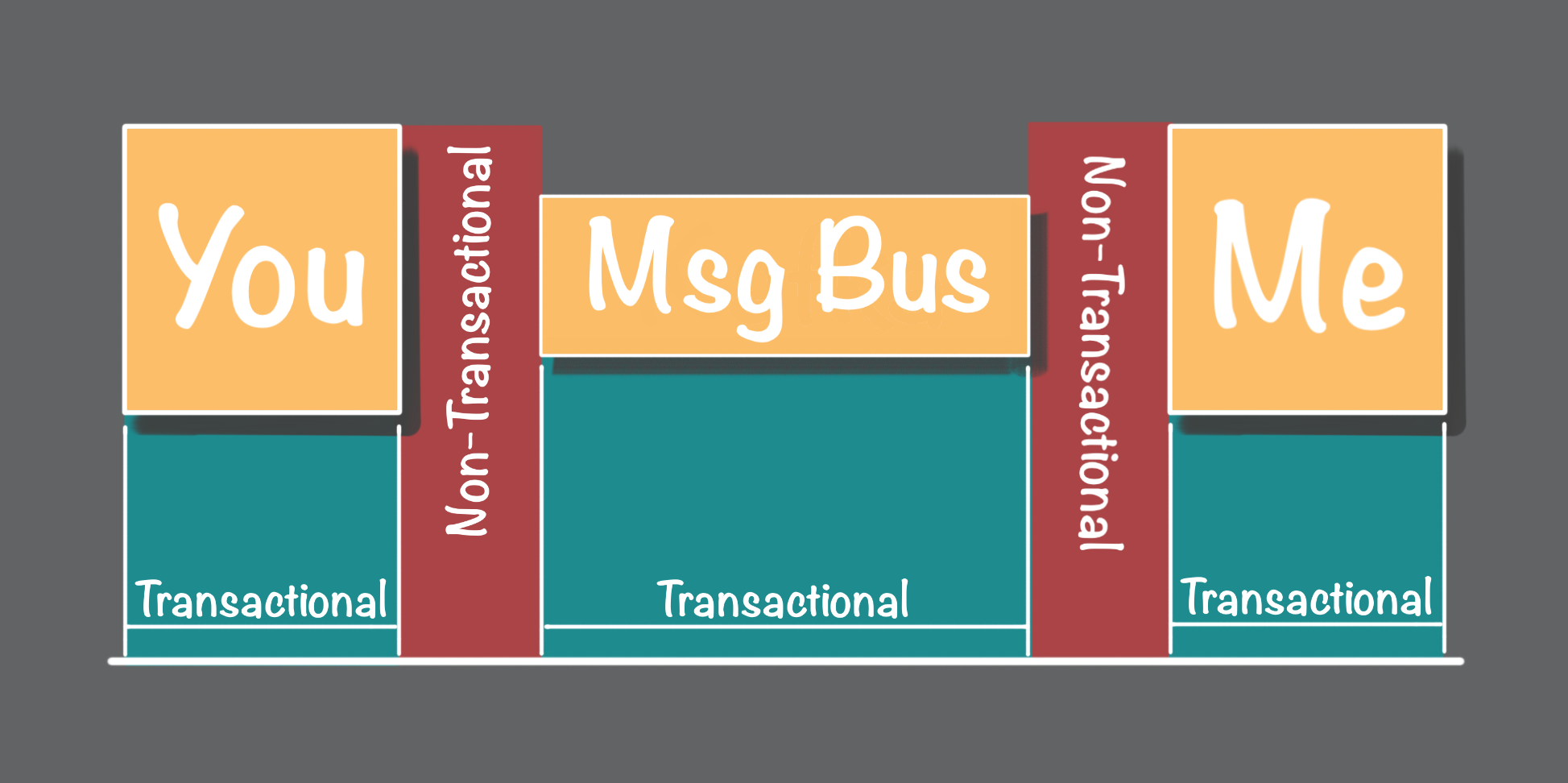

First, let's set the playing field in our order and shipping example scenario. On your order processing end, you store the state of orders in a local persistence store. On my end, I've got another local to me persistence store for maintaining the state of the order shipping processes. In between, we have a message bus, such as Kafka, Pulsar, ActiveMQ, and many other pub-sub and queue brokers. To be clear, we each have our independent persistence stores, and we cannot perform any single transactions that spans our two persistence stores.

The message bus also provides transactional guarantees. Once a given message is successfully delivered to the message bus it guarantees that message is eventually delivered to the message receivers or consumers. One of the challenges in this message delivery flow is the non-transactional gaps between the event bus and the message senders and receivers, as shown in above image. The details for handling this were also covered in at-most-once.

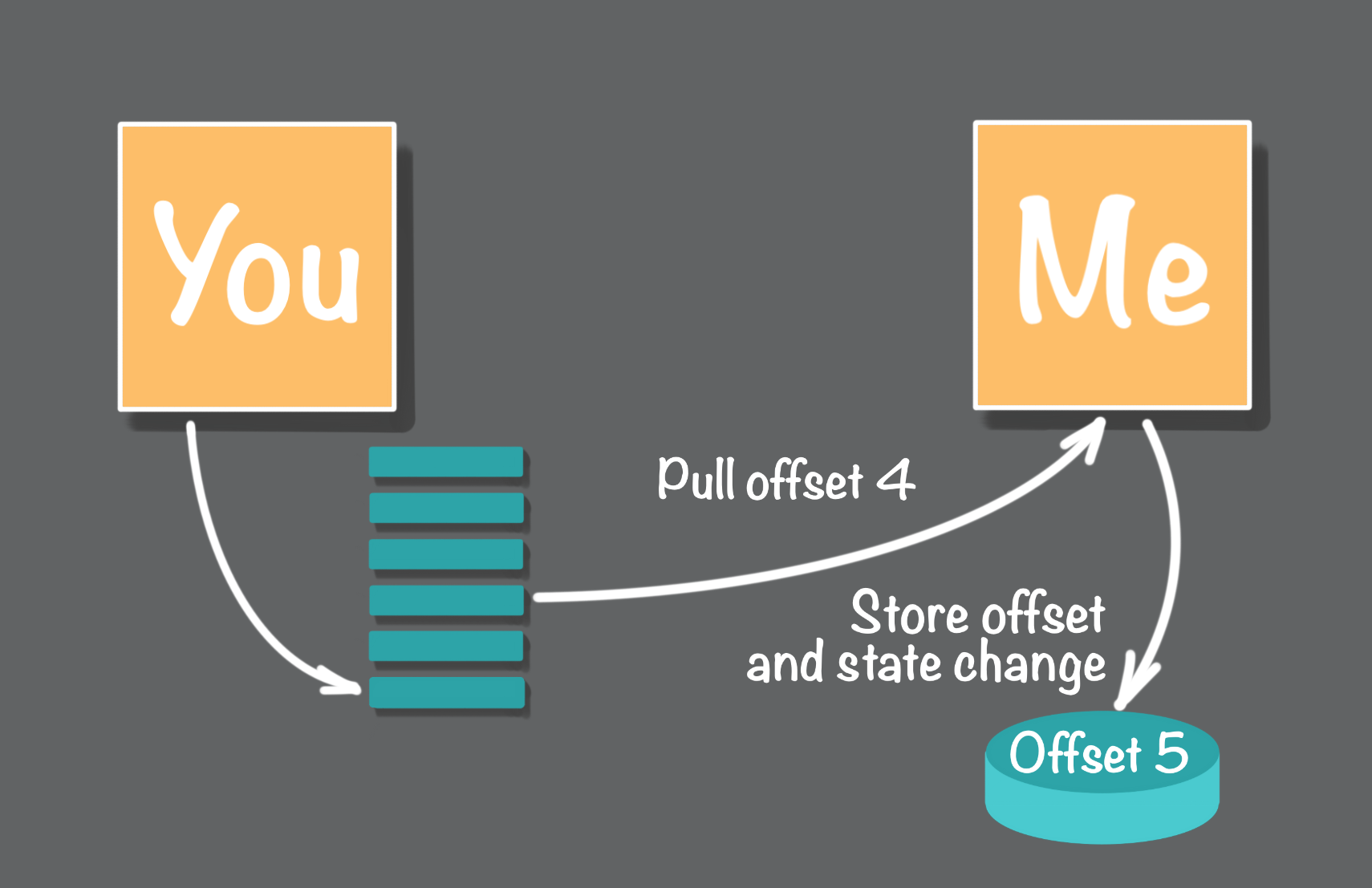

An essentially-once solution is to use the pull approach where the message producer logs all messages, and the message consumers each maintain an offset that points to the next message to be consumed, as shown in above image. The essentially-once “trick” is for the message consumer to persist that offset in the same transaction used to persist the state change. This transactional pull approach nicely handles failures. A message is pulled from the log at the current offset. Then the state change operations are performed. When a failure occurs after a message has been pulled, but before the transaction is committed, the message consumer will restart after the failure at the same non-updated offset.

For other alternative approaches to implement Essentially-Once Messaging, please visit lightbend: exactly-once

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source: