At-Most-Once

Disclaimer: This note is mostly inspired by the Lightbend: How Akka Works series

The at-most-once message delivery approach means that when sending a message from a sender to a receiver there is no guarantee that a given message will be delivered. Any given message may be delivered once or it may not be delivered at all. Any attempt to deal with a failure to deliver a message is crossing into the at-least-once message delivery territory.

This maybe-once delivery approach is analogous to you sending a message via a text message or letter using the postal service. In either case, once you send the text or post the letter you do not attempt to verify that the message was delivered to me. Using the at-most-once approach for message delivery is acceptable in many cases, especially in situations where the occasional lose of a message does not leave a system in an inconsistent state.

Overview

With a synchronous object method invocation, the caller knows when the called method is done when the method call returns. When sending an asynchronous message, such as sending a message to an actor or to a microservice, the sender only knows that an attempt was made to send the message. There is no indication that the target recipient received the message.

This is how the at-most-once message delivery process works. An attempt is made to send a message to the receiver. However, there are no guarantees that the message will be delivered. Any number of things may happen that prevent the successful delivery of an asynchronous message.

It is possible for the recipient to send a reply back to the sender but this is a deliberate action done by the receiver and not a natural action that occurs as with an object method call. Also, as with the attempt to send the initial request message, sending a response message may not be received.

Asyn Message Flow

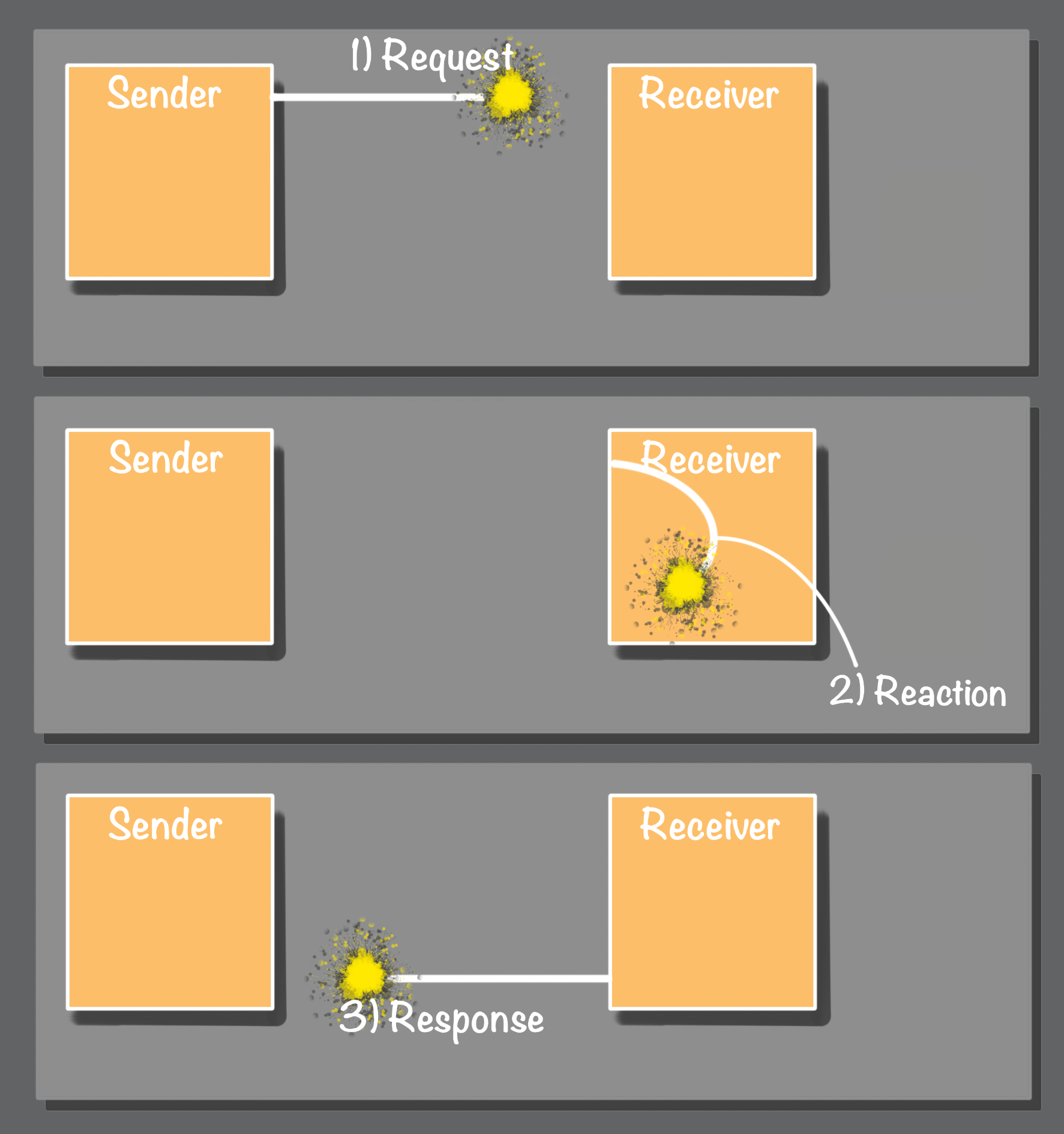

The process involves three distinct steps.

- The sender sends an asynchronous message to the receiver.

- The receiver performs some reaction operation when the message is received.

- The receiver sends an asynchronous message back to the initial sender.

In this three step process, there are three opportunities where a failure will break the asynchronous request response cycle. The initial message may never be sent to the receiver. The receiver may get the message, but it may fail before it can send a response back to the sender. Finally, in the third leg of the journey, the receiver may attempt to send a response message back to the sender, but the response message is never received.

Failure

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Most Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Most Once' Message Delivery

From the perspective of the message sender, there are no clues as to where the failure occurred. As shown above, a failure may occur in any one of the three legs of the request to response journey. One of the biggest issue is that the sender does not know if the receiver performed the requested re-action. There is no indication that the failure happened before, during, or after the receiver reacted to the message. In situations where the receiver is performing an operation that must occur, like persisting a required state change, the sender has no idea if the state change happened or not.

Is there a difference between synchronous or asynchronous message delivery in regards to reliability?

In short, using either a synchronous or an asynchronous messaging approach has no real impact when dealing with failures.

For more information: How Akka Works: 'At Most Once' Message Delivery

Use cases

TL;DR - It is suitable for use cases like monitoring metrics, where a small amount of data loss is acceptable.

While there are certainly differences between sending messages synchronously versus asynchronously, the primary consideration here is what is happening on each end of the conversation. What you need to consider is this, are you trying to synchronize state changes on both sides of the conversation or not? Using at-most-once messaging is fine when there is no need to synchronize state changes between the message sender and the message receiver. However, using at-most-once message delivery when it is necessary to synchronize state changes will burn you when things break.

The fatal flaw with at-most-once delivery is that the problems only crop up when things break. When everything is working correctly, the message flow is not interrupted, and no messages are lost, which means synchronized state changes happen as they should. This all falls apart when things break, and some messages are not delivered. These message delivery failures will result in corrupted system state.

Consider the order and customer processing scenario. When an order is created the customer must be notified. The act of creating an order is a state change. When an order is created, it notifies the customer. This notification triggers a customer state change. The customer state change then triggers an event that causes the order to do another state change.

The sequence of events is a new order is created in the “new” state. The customer updates the “credit limit” state. This finally triggers the order to be changed to an “approved” or “canceled” state.

In this scenario, there are two messages that must be delivered, the initial order-created message and the credit-approved or insufficient-credit message. When either of these messages is not delivered the state of the system is corrupted.