At-Least-Once

Disclaimer: This note is mostly inspired by the Lightbend: How Akka Works series

TL;DR - With this data delivery semantic, it’s acceptable to deliver a message more than once, but no message should be lost. While not ideal from a user perspective, at-least once delivery semantics are usually good enough for use cases where data duplication is not a big issue or deduplication is possible on the consumer side. For example, with a unique key in each message, a message can be rejected.

Overview

With the at-least-once approach for sending messages either the message sender or the message receiver or both actively participate in ensuring that every message is delivered at least once. To ensure that each message is delivered either the message sender must detect message delivery failures and resend upon failure, or the message receiver must continuously request messages that have not been delivered.

Either the message sender is pushing each message until the message receiver acknowledges that the message was received, or the message receiver is pulling undelivered messages.

Why do we have at-least-once when exactly-once seems to be a much better solution?

As we just briefly discussed, with the at-least-once messaging approach, the best we can do is implement processes that may result in the delivery of some messages more than once.

Conceptually an exactly-once message approach is much more desirable. But, as the saying goes, “you can’t always get what you want.”

For now, consider that implementing an exactly-once messaging solution is on the same level as creating a vehicle that can travel faster than the speed of light. There are ways to get close, that is to deliver messages essentially-once but it is impossible to implement an exactly-once process that works.

In the exactly-once page, we will look at this in more detail.

Scenario

Consider this scenario. You and I are exchanging text messages. I need to send you an urgent text message. I send you this urgent text message and to ensure that you have received it I’m expecting an acknowledgment response text message from you.

Acknowledgment (or "ack"). A signal sent by a subscriber to Pub/Sub after it has received a message successfully. Acknowledged messages are removed from the subscription message queue.

The ideal sequence of events is that I send you this urgent text message, you read it, and then you send me an acknowledgment text message that lets me know that you have received my message. This is the happy path where everything works as expected. However, there is also the sad path where something occurs that prevents this exchange of text messages from happening as we expected.

The fundamental challenge here is that when I do not receive an acknowledgment from you, I have no way of determining if you have received the message. Multiple failure scenarios will happen that result in the failure to receive an acknowledgment message. One of the failure scenarios is that you did receive the urgent text message but were unable to send me an acknowledgment. From my perspective, there is no way for me to know if you did or did not received the message. As a result, I am forced to resend the urgent text message again and again until I hear back from you. Also, as a result, you may receive my message more than once.

Workflow

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

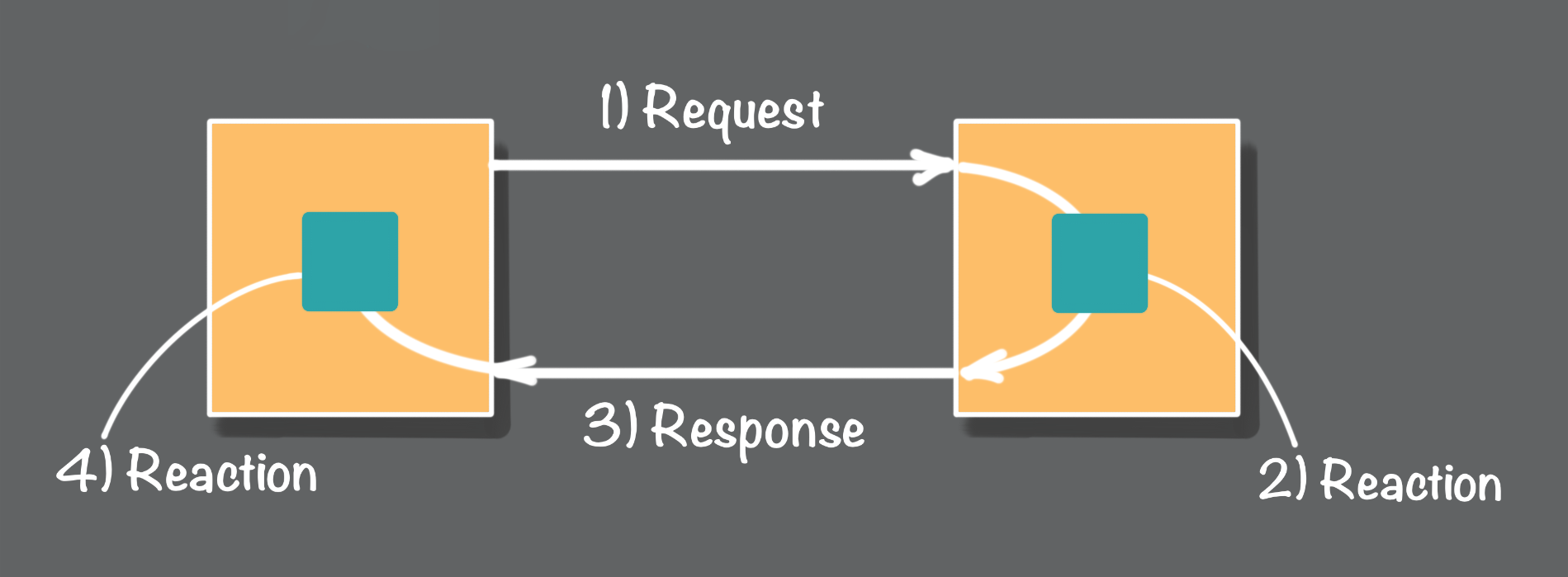

There are at least four distinct steps in the message request and response cycle.

- Send a request message across the network from the sender to the receiver.

- The message receiver reacts in some way to the request message.

- The message receiver sends a response message over the network to the sender.

- The message sender reacts to the response message.

To check the exaplination of how above 4 steps fail, visit How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

From the perspective of the message sender, any one of these failures will indicate that something went wrong, but when failures do occur, it is impossible to know if the message receiver reacted to the message or not. Also, consider the failure scenario at stage 4. The message sender has received a response message, but it failed before it properly handle the response. When the sender is restarted there is no evidence that a response was received. Again, from the perspective of the message sender, it is as if the initial request message was not sent.

When failures do occur, the sender has no choice but to send the message again. As we can now see depending on where in the sequence a failure did happen there is the possibility that the same messages will be sent multiple times to the receiver.

Use Case

TL;DR - With at-least once, messages won’t be lost but the same message might be delivered multiple times.

While not ideal from a user perspective, at-least once delivery semantics are usually good enough for use cases where data duplication is not a big issue or deduplication is possible on the consumer side. For example, with a unique key in each message, a message can be rejected.

2 ways to implemente

There are at least two ways to implement message delivery processes that guarantee at-least-once delivery of every single message. There is a push approach and a pull approach. As the name implies, with the push approach, the message producer pushes messages to message consumers. The alternative is the pull approach where the message consumer pulls messages from the message producer.

Push at-least-once Message Delivery

With the push approach, the burden of responsibility for at-least-once message delivery falls on the message producer. Let’s use person to person texting as an example again to explore the mechanics of the process.

Consider the case where you are trying to send a message that must be delivered to me, and there is a problem that is preventing the successful delivery of that message. Ok, one of the first things that you can do is implement a retry loop, where you retry the delivery of unacknowledged messages until you have confirmation that they have been delivered to the receiver.

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

That should work, right? Well, you need to ask yourself what can go wrong? When you are designing for reliability you must face facts; things will break. Software, servers, and networks will fail. And some of these failures will happen at the worst possible time. Like when one or more undelivered messages are currently stuck in a retry loop.

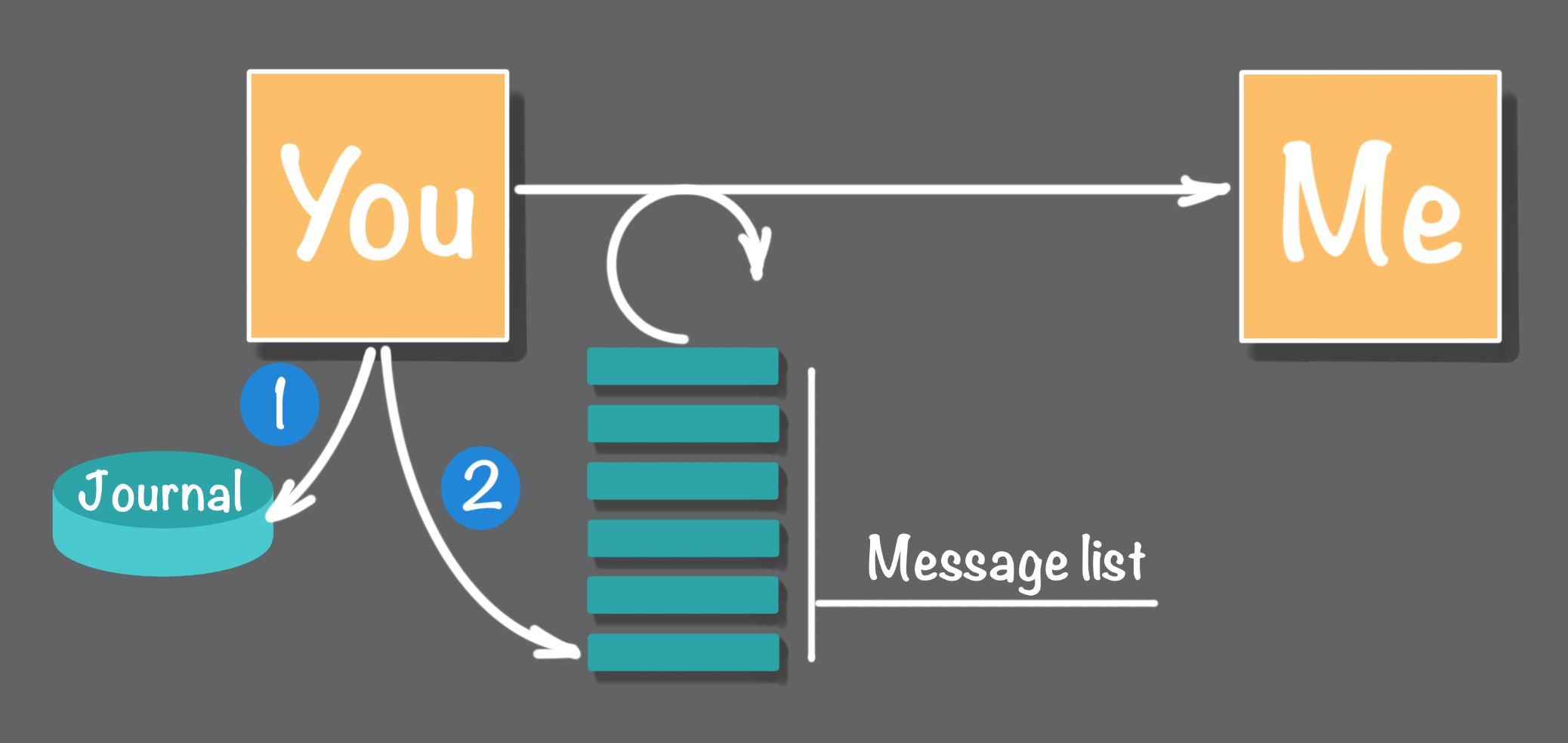

Adding state(journal) to overcome vulnerability

Given that it is bad if you go down while undelivered messages are stuck in a retry loop you need to do something that will prevent the loss of undelivered messages in the event of a failure of the message producer. One solution is first to place all to be delivered messages into a persistent list or queue before you try to send each message to the receiver.

Now that you have a persistent place to store undelivered messages do you have a solid design? Not really. Consider that something had to happen that triggered the need to send a message in the first place. In our texting example, say that you performed some task that triggered the need for you to send me a message.

Say you are keeping a journal that records all of the people that you are tasked with sending these urgent must be delivered text messages. The result is that each time you receive a request to send someone a text message. You need to

- first record this task in your journal

- then add the pending message to the list of to be sent messages

Implementation

In a software implementation of this process, this would be implemented as two distinct database transactions, one transaction that adds a task to a journal and second transaction that adds the message to a persistent list or queue.

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Now you have this two-step process that records tasks in a journal and adds the corresponding message to a to be delivered list. Are there any vulnerabilities here? What will go wrong? For the vulnerablilities of this push approah, visit How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

In short, it's so complex to build a reliable message delivery processes with push. There are ways to implement more reliable message delivery processes. One approach that is often much less complicated to implement is the somewhat counterintuitive pull approach. This is what we will be looking at in the next section.

Pull at-least-once Message Delivery

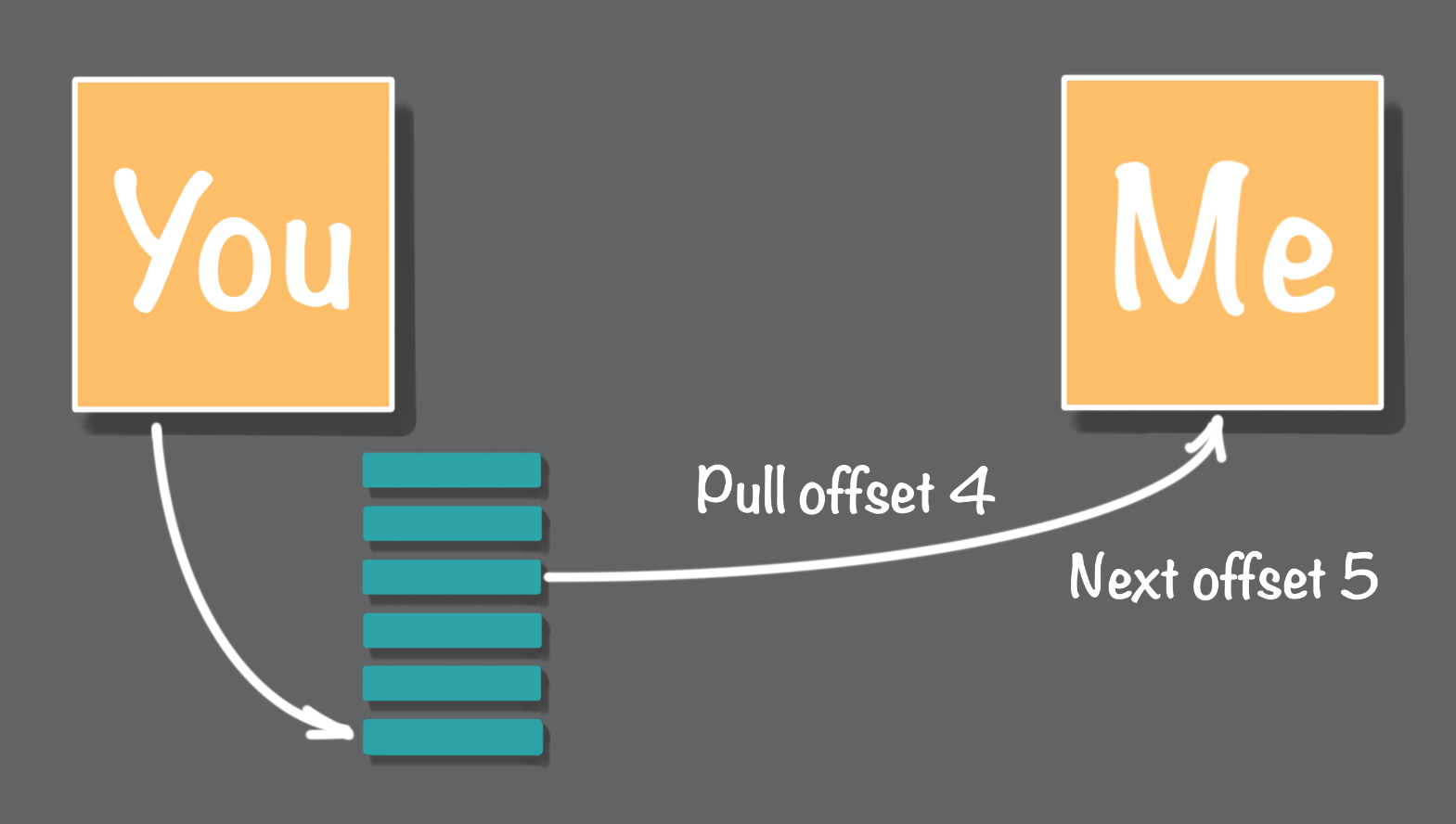

With the pull approach, we still have a message sender or producer, and we also have a message receiver or consumer. However, the actual process that is used to transmit messages from the producer to the consumer is flipped. Instead of the message producer actively pushing messages to the consumer, it is the consumer that assumes the primary responsibility for retrieving messages from the producer.

For implementations of the pull approach, the message producer’s primary responsibility is to place all messages in a list or log. The consumer’s responsibility is to maintain a pointer or offset into the producer’s log that identifies the next message to be transmitted and processed. As the producer is consuming messages, in below image, the offset is incremented to the next message.

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

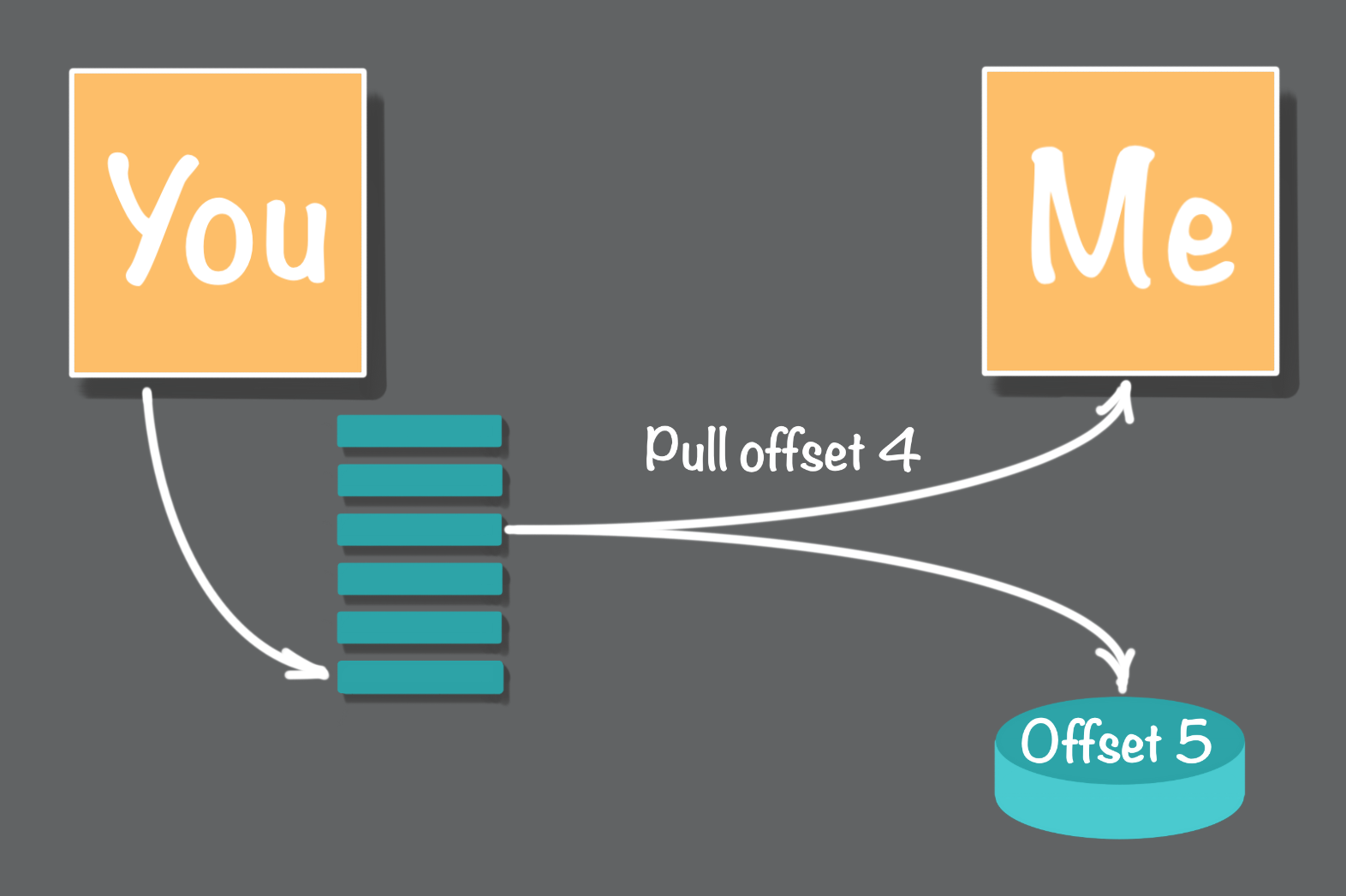

Adding state(offset) to overcome vulnerability

The next message pointer or offset must be managed in a way so that when the consumer is restarted the current value of the offset can be recovered, which requires that the offset is persisted.

In the case where the message consumer is performing persistent state changes when processing messages, an important consideration is the combination of the step for persisting the state change and the step for persisting the current offset. Ideally, both of these steps can be combined into a single transaction; this solution is about as good as it gets because this is an effectively-once message delivery implementation.

When it is not possible to combine these two steps into a single atomic operation, then one possible solution is that the persistence of the offset follows the state change persistence step. This two-step process, as shown in below image, requires that the first step is idempotent. That is when the same message is processed more than once the outcome of the first step is the same.

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Source: How Akka Works: 'At Least Once' Message Delivery

Here is an example of a process that must be idempotent but is challenging to implement. Consider that the messages sent to the consumer are bank account deposits or withdrawals. The state of the bank account is altered and persisted when these deposit and withdrawal messages are processed. Obviously, it is essential that each bank account cannot be corrupted with duplicate deposits or withdrawals.

How to be idempotent to eliminate duplicate messages

So how do we eliminate duplicate messages that cause cumulative state changes? The answer is that some evidence that a given message has been processed must be recorded as part of the cumulative state change’s transaction. This evidence could be persisting the current message offset in the same transaction. Another approach is to store all or part of the message itself so that incoming duplicate messages may be eliminated. One more strategy is first to log each incoming message, which then triggers the cumulative state change operations as a follow-on step. This final approach is known as event logging. We will look at this in detail in the exactly-once page.

Push versus Pull at-least-once Message Delivery

Both the push and the pull at-least-once message delivery approaches are commonly used, and each has their strengths and weaknesses. Often, however, the pull approach tends to easier to implement.

There are some common features and considerations for both message delivery approaches.

- For both push and pull implementations the message producer is responsible for maintaining a list or queue or log of messages. When pushing messages, this list is used to retransmit messages that have so far failed to be delivered. When pulling messages, this list is used by the message consumer to retrieve and process pending messages.

- Another common feature for both the push and pull approach is that the consumer may have to implement some form of idempotency. Idempotency is essential when the same message is delivered more than once to a message handler that performs state changes, such as a bank account message example previously discussed.

You can now go to the exactly-once page. While theoretically, an exactly-once approach for message delivery is appealing once we look into the challenges and limitations I think you will see that the at-least-once approach is a more practical way to go.