Limitations of the Scientific Method

Recently delving into various psychology books, I stumbled upon an intriguing concept: how psychologists test their ideas. It struck a chord because, let's face it, humans are a tough bunch to predict. Coming from a computer science background, I recognized a similarity between measuring an AI algorithm's performance and understanding human behavior. We isolate variables in a simulator to gauge the AI's efficiency. But what about us? How do we establish theories on the cause-and-effect of human thoughts and reactions using scientific methods?

That's the fascinating topic I want to explore based on what I've been reading in some books. It's a quest to unravel the mysterious workings of the human mind and how psychologists apply methods akin to those used in computer science to make sense of it all. Let's get started!

Intro

The research methodology used in modern psychology is no different from natural sciences. It heavily relies on substantial data to support scholars' claims. Simply put, the ability to argue for or against certain psychological phenomena depends on the presence of data. Without data, mere speculation becomes unconvincing. Relying on data is what we often refer to as the scientific method. Applying this method to solve problems is empirical research. In empirical research, scholars pursue cold, hard numbers, a natural expectation in the realm of natural sciences as natural phenomena are just that—impersonal.

However, when the same mindset is applied to humans, many find it hard to accept. They believe humans possess warmth; human thought isn't just material, it has spirituality and more. While this view might not be wrong, psychologists suggest that if people strongly adhere to this belief, thinking that humans cannot be measured by numbers, then formal university psychology courses might not be suitable. They might feel their mental space constrained because they cannot analyze any psychological phenomena solely based on subjective experiences. It's not a fault of these individuals or the current direction of psychological thought; it's just a mismatch of thoughts.

Materialism and Dualism

There are two distinct perspectives on how we perceive the world.

Dualism

The first is known as dualism, believing that the human world comprises two substances: physical matter that we encounter every day and another substance—mental matter. Mental matter, intangible like energy, includes entities like the soul. Dualists see the human body as a physical vessel connected to the soul, where human thoughts and behaviors manifest from the soul and consciousness.

Materialism

The second perspective is materialism. Those who adhere to materialism argue against the existence of intangible entities like the soul since they can't be measured or quantified. According to them, debating their existence is futile, and it's simpler to believe that the world consists only of visible matter. Under materialistic thought, anything seemingly intangible in humans, like thoughts or consciousness, is a result of the functioning of the brain, a physical organ. If the brain were fully understood, scientists could unravel the mysteries of consciousness or intelligence.

Materialism serves as the foundation of scientific thought. From a scientific standpoint, science only studies issues that can be studied, measured problems. Any topic temporarily beyond scientific study is avoided and remains unsolvable by science. Materialism, evolving with the world after the industrial revolution, has become the mainstream thought in the scientific community. It's noteworthy that many scientists have religious beliefs, believing in God and the existence of souls. However, when they conduct academic research, they strictly follow scientific thinking. These personal beliefs and professional work don't necessarily conflict.

What is matter in materialism?

Here's an intriguing yet unanswered question for readers to ponder: Materialism is based on what humans can see, hear, touch, and measure. However, the ability to measure a substance relies on the instrument's capability. What are our "instruments" for sensing the physical world? Our eyes, ears, and other sensory organs. The problem is that these "instruments" are not omnipotent; they cannot sense all stimuli in the natural world. For instance, humans can only hear sound frequencies between 20Hz and 20,000Hz. Does that mean what we can't hear doesn't exist? Certainly not. Similarly, our eyesight operates within a specific wavelength range in the visible spectrum. Does that mean what lies beyond this spectrum doesn't exist? Again, not necessarily.

So, what exactly is the "matter" in materialism? How should we define it? This question is left for us to contemplate.

Research methods in psychology

The three main research methods frequently used in modern psychology for quantifying behavior are as follows:

Surveys

Surveys constitute the first method used. When talking about surveys in academic research, it's often misunderstood as similar to market research surveys seen in daily life, with questions arbitrarily set by researchers. In psychology, however, surveys comprise various psychological scales that have been validated and proven reliable through statistical methods. Accuracy ensures questions precisely measure intended psychological constructs like motivation, empathy, or happiness. Reliability ensures consistent results, preventing fluctuations when a participant retakes a survey.

Psychological scales measure internal psychological variables that are challenging to directly assess externally, such as personality traits, life meaning, mindset, materialism, altruistic tendencies, etc. Each scale contains a set number of items used for measurement. For example, in personality measurement, researchers might employ the HEXACO scale, consisting of 60 items measuring six personality facets. Participants respond to these items based on a scale (e.g., from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree), providing quantifiable data. Researchers then analyze this data statistically to draw conclusions.

Experiments

Experiments focus on studying how a single variable affects a target variable. They aim to establish causal relationships between independent and dependent variables. Independent variables represent the "cause" studied by researchers, while dependent variables represent the "effect." A well-designed experiment ensures that only the independent variable changes while controlling all other potential variables throughout the process. For instance, in a study on how a smile influences first impressions, the smile constitutes the independent variable, and the formation of first impressions is the dependent variable. Through rigorous control, experiments quantify the relationship between these variables, a feat not easily achievable in survey-based studies due to a lack of environmental control.

Neuroimaging

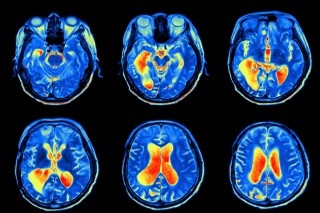

Source: Neuroimaging and Depression

The third method for quantifying target variables in psychological research emerged in the last three decades—brain imaging. Due to technological advancements, neuroimaging methods have gradually been applied in psychology. Since psychological processes stem from brain operations, studying brain activity becomes crucial. Instruments like electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) quantify various brain activities, aiding in statistical analyses to understand which brain regions are more active during specific cognitive processes.

Limitations of Relying on Quantitative Data(定量數據)

Where does the reliance of modern psychological research methods on quantitative data fall short?

Human thoughts and behaviors are more than just numbers

Firstly, this is frequently questioned by other disciplines within the humanities and social sciences. They argue that human thoughts and behaviors shouldn't be solely expressed through numbers. Human behavior is highly complex, and summarizing it with a single value isn't appropriate. This disagreement largely stems from differing paradigms across various professions, reflecting fundamental differences in thinking patterns. Just as psychologists often criticize other social sciences for leaning towards abstract concepts lacking empirical support, this point remains contentious. Therefore, I won't dwell much on this aspect. What I'd like to highlight is that individuals from different fields shouldn't let their professional training limit their capacity to accept diverse perspectives. Everyone should keep an open mind, learning from various disciplines and not allowing barriers to grow thicker between fields.

Quality Variances in Survey Responses

The second issue pertains to problems with survey research. Although surveys are advantageous in measuring certain deeply embedded psychological structures, it's understood that various issues arise when participants respond to surveys. Firstly, participants aren't constrained when answering surveys; they are entirely free in their responses. Therefore, researchers find it challenging to ensure whether participants are focused, comprehend the questions clearly, or even respond honestly. While researchers have methods to assess whether participants provide dishonest answers, it doesn't guarantee that participants are answering earnestly. For instance, if a participant is aware of their narcissistic personality tendency, and considering narcissism is viewed negatively, they might intentionally conceal this tendency in some questions to present a false answer. This behavior is known as social desirability bias.

Pitfalls of Experimental Research

The third issue lies in the essence of experimental methods. Psychological experiments, like other natural sciences, need to be conducted in highly controlled environments. Such control allows researchers to establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

What does cause-and-effect mean? It implies that changes in the measured variable (dependent variable) inevitably stem from a variable controlled by researchers (independent variable). To achieve this cause-and-effect relationship, researchers must control all variables that might affect the dependent variable. For readers unfamiliar with experimental research, seeing numerous variables might seem overwhelming. Let's explain using an example.

For example, a researcher wants to do a research to examine the impact of materialism (the belief equating material indulgence with happiness, success, and the central focus of life) on behavior. One hypothesis was that highly materialistic individuals might find strangers less trustworthy. Then the researcher need to validate the consequence of materialism (independent variable) leading to "dislike towards others" (dependent variable) using an experiment.

Throughout the experiment, the researcher has to keep all variables related to "dislike towards others" constant, allowing participants to experience changes in only one dependent variable. In the experiment, participants were randomly divided into two groups. One group was exposed to images of luxury items to evoke their materialistic values, while the other group viewed natural scenery photos to suppress their materialistic beliefs. After both groups viewed the respective images, they were asked to rate a series of portraits on "trustworthiness." This allowed the researcher to attempt establishing a causal relationship between materialism and the formation of first impressions of others.

Undoubtedly, the causal relationships produced through experimental research hold scientific significance. Essentially, all sciences aim to unravel causation to understand the essence of things. However, humans are intricately social creatures, in constant interaction with diverse environments, people, and circumstances. Even if the quality of an experiment is unparalleled, there remain criticisms about the results derived in highly controlled, "artificial" settings in psychology. Can these conclusions explain or predict human thoughts and behaviors in the diverse, ever-changing real world?

Sample Representativeness Issue

Continue the above topic of limitations of relying on quantitative data, the issue of sample representativeness in contemporary psychological research (whether in surveys or experimental studies) is frequently criticized. What is a sample? To understand what a sample is, one must first grasp the concept of a population. Psychology is the study of human behavior, and the most ideal way to gather data involves collecting information from every member of the population you're interested in, and then conducting statistical analyses to draw conclusions. For instance, if a researcher wants to understand women's perceptions of materialism, the best method would be to send surveys to women in every corner of the world, inviting them to fill out the questionnaire. This way, the researcher could acquire data representing the entire population of interest (all women worldwide), and their data would genuinely reflect the reality.

However, is it possible to collect data from the entire population? Certainly not. No one has the capability, time, money, or resources to gather data from every member of a population.

The next best option

Since it's impossible to obtain data from the entire population, researchers resort to the next best option: sampling from the population and using statistical techniques to infer the real data of the entire population from the sample's results. Theoretically, this method of inferring population data from sample data is viable as long as the research sample is randomly drawn from the population. Employing random sampling ensures a highly representative research sample, meaning the data from the sample can reflect the real data of the population.

According to statistical theory, for instance, to represent the population data of Hong Kong's 7.5 million people, a sample of around 3,000 randomly selected individuals would suffice. Simple in theory, the challenge lies in the fact that * random sampling is a rather complex, time-consuming, costly, and idealistic endeavor*. To achieve ideal random sampling, one would need access to the phone numbers of all Hong Kong citizens, then use a computer program to randomly select 3,000 phone numbers and invite those individuals to participate in the study. Ideally, all 3,000 selected individuals would immediately agree to participate, ensuring a highly representative sample.

However, reality often differs from this ideal scenario. A significant portion of those 3,000 individuals would likely decline to participate. To reach the desired sample size of 3,000, researchers would continue randomly selecting phone numbers and inviting more people to participate until they reach the target number. One can imagine that the group of 3,000 individuals who agree to participate already has a certain bias. Perhaps this group tends to have higher education levels and is more inclined to engage in scientific research, thereby not representing the entire population, especially individuals from lower educational backgrounds.

Convenient sampling & WEIRD

As ideal random sampling is time-consuming and challenging, coupled with significant competition in academic research, scholars often prefer not to bear these costs. Therefore, in psychological research, most academic studies' samples come from what can be termed as "convenient" sampling. This sampling method is referred to as convenient sampling. Just like psychologists worldwide, a researcher most easily accesses the group of college students or young adults aged 18 to 21. As a result, the sampling in contemporary psychological research is often criticized, a phenomenon referred to as the WEIRD effect in the literature.

WEIRD stands for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. The "Educated" sample bias, as previously mentioned, occurs because psychologists, for convenience, tend to recruit their students or college students as research participants. The biases related to "Western," "Industrialized," "Rich," and "Democratic" can also be understood together. Due to historical reasons, most academic research is led by developed countries, primarily from advanced Western countries and regions.

Even though Eastern countries or regions have made significant contributions to psychological research in the past three decades, Western countries continue to maintain a leading position in terms of quantity and impact. Due to the biases in samples, when interpreting findings from a single psychological study, caution is essential. Psychology is the science of human beings, and when one's background differs (such as education, race, gender, etc.), the same psychological conclusions may not necessarily apply to everyone.

Understanding Psychological Research Conclusions

From the above, it's clear that no method of quantifying data is perfect. Some might ask, "Doesn't this mean psychological research isn't reliable?" Here, it's crucial to understand that no psychological study can be perfect. Each theory in psychology isn't invincible; it can only be applied to certain contexts. So, how should we interpret conclusions from psychological research? There are misconceptions about understanding psychological theories and interpreting research conclusions, and it's essential to address them here.

Mistake 1: Confusing "Correlation" with "Causation"

For instance, common headlines like "More books at home lead to better children's grades," "More exercise leads to longevity," or "Taller people have higher incomes." People often assume these statements indicate a cause-and-effect relationship. However, it's important to note that causation requires highly controlled and rigorous experiments to establish. Conclusions drawn without experiments are merely correlations. For instance, having more books at home correlates positively with better grades, but it might not establish causation. Many third variables, like higher-educated parents in book-filled homes leading to a better economic environment, can influence this relationship.

Mistake 2: Assuming Theories Are Always Correct or Useless Otherwise

The term "theory" implies that it's not necessarily always correct. Each theory applies only to explaining behavior or phenomena within specific environments. For instance, you can't use Sigmund Freud's theory to explain visual information processing. Theories aren't omnipotent; they all have limitations. Even something as great as Newtonian mechanics has its application limits, let alone psychological theories.

Mistake 3: Misusing Subjective Experience to Challenge Theories

For example, someone might counter the statement "Taller people have higher incomes" by saying, "I'm not tall, but I earn more than many tall people! How do you explain that?" As researchers, observing such challenges based on personal experiences can be frustrating.

- Firstly, research conclusions are based on statistics, which inherently involve individual differences and data variances. Thus, conclusions don't apply to every individual; they represent the majority statistically.

- Secondly, subjective experiences might lack academic grounding and often constitute random, personal, and subjective observations. Using such unsystematic experiences to understand theories isn't meaningful.

Summary

In summary, psychology differs from philosophy; it studies human behavioral topics that can be scientifically researched. Complex real-life issues must be simplified to a level research can handle. Therefore, individual research results/theories cannot reflect the entirety of reality. Theories aren't always correct, and they can be challenged. However, when challenging a theory, it's crucial to discern whether the challenge comes from purely personal subjective experiences or observations grounded in academic research.

The scientific method isn't perfect, but it's presently the most objective approach available

The preceding discussion highlighted the limitations of the scientific method. Indeed, psychology is a human science, and human thoughts and behaviors are highly complex. What's more important is that the scientific method is a problem-solving strategy, and every strategy must have its flaws. I must emphasize repeatedly that the problems that science cannot currently solve (such as what consciousness is, how consciousness can be observed or regulated) do not imply that those problems do not exist or cannot be resolved. Sometimes, it might just be that current technology isn't advanced enough, leaving scholars at a loss.

Just as fifty years ago, psychologists couldn't imagine that fifty years later, they would be able to directly observe the functioning of brain cells using various technologies. Despite the potential limitations of today's scientific methods, the author believes that observing human thoughts and behaviors through an objective and empirical approach is more convincing than subjectively guessing the reasons behind human thoughts and behaviors based on emotions. Therefore, I urge all readers to stay vigilant as it's quite possible that within fifty years, due to technological breakthroughs, we'll be able to directly understand the workings of the brain, consciousness, and the mysteries of the soul."

Reference

- 別誤會,心理學不是這樣的 by Lo’s Psychology