Atkinson and Shiffrin's Three-Stage Memory Model

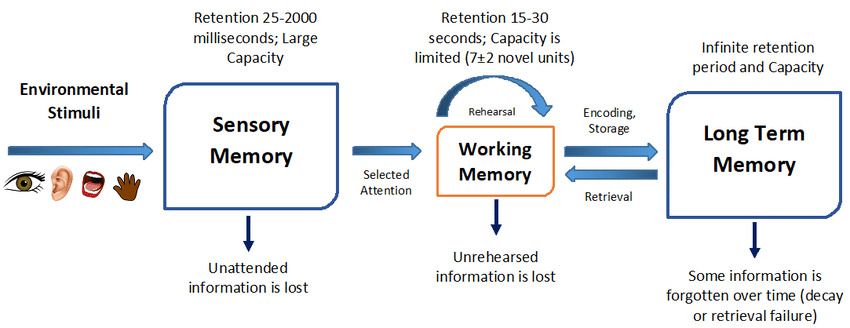

Understanding how memory functions is a complex endeavor, but models such as Atkinson and Shiffrin's Three-Stage Memory Model help us conceptualize the process of how we encode, store, and retrieve information. Introduced by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin in 1968, this model has formed the foundation of our understanding of memory for many years. The model explains memory in terms of three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory (which they also referred to as "Working Memory"), and Long-Term Memory. Let's dive into each of these stages to better understand how our memory works.

Source: ResearchGate

Sensory Memory

Sensory memory is the earliest stage of memory. At this level, the sensory information from our environment is stored for a very brief time. Sensory memory acts as a buffer for stimuli received through the five senses. This type of memory allows individuals to retain impressions of sensory information after the original stimulus has ceased. It is an automatic process and not under conscious control.

Characteristics of Sensory Memory

- Capacity: Sensory memory can hold a large amount of information, but only momentarily.

- Duration: The information is typically retained for less than a second for visual information (iconic memory) and around 3-4 seconds for auditory information (echoic memory).

- Function: This stage serves to give the brain some time to process the incoming information and decide if it is worth attention. If attention is given, information may then move on to the next stage.

Example of Sensory Memory

To illustrate sensory memory, imagine you're glancing at a landscape. The visual details—the colors, shapes, the way the light falls—all flood your senses. Almost immediately, these details begin to fade, but for a fraction of a second, you retain a vivid impression of the scene. That lingering perception is sensory memory.

Short-Term / working Memory

Short-term memory (STM) is a temporary storage system where information is held while it is needed for current cognition, often for less than a minute. At this stage, only a small amount of the information in sensory memory is transferred to STM.

Example

Consider you meet someone and learn their name. If you repeat the name to yourself and focus on it, you're using short-term memory to hold onto the information. Without any active effort to retain it, you might forget the name within seconds or minutes.

Characteristics

- Capacity: STM is limited. According to Miller's Law, most people can hold between 5 and 9 items in their short-term memory.

- Duration: Typically, STM lasts about 20 to 30 seconds without rehearsal. Rehearsal can keep information in STM longer.

- Function: It's used for immediate tasks, such as holding a phone number in mind while dialing.

- Encoding: Information in STM is mainly encoded acoustically (by sound) or visually.

Elaborative rehearsal

- Maintenance Rehearsal: Repeating the information mentally to keep it in short term memory longer but it will eventually fade out. Since it is a shallow(淺層) information processing method, It can't turn the memory into long term memory.

- Elaborative Rehearsal: It is a technique for improving memory by forming associations between new information you're trying to learn and information you already know. The goal is to integrate the new knowledge deeply into your long-term memory by creating meaningful links.

Here's how you can use elaborative rehearsal to turn short-term memories into long-term ones, with an emphasis on self-involvement:

- Find Personal Connections: Relate the information to your personal experiences or emotions. For instance, if you're trying to remember a historical event, think back to what you were doing around that time, even if it's not directly related. Making it personal helps cement the memory.

- Deep Processing: Instead of simply repeating the information to yourself (rote rehearsal), think about its meaning and implications. Ask yourself questions about the material: "Why is it important?", "How does it work?", or "What problem does it solve?"

- Teach What You've Learned: Try to explain the concept or information to someone else in your own words. Teaching requires a comprehensive understanding of a topic, and in the process of making it clear to others, you'll often solidify your own memory of the subject.

- Use Mnemonic Devices: Create acronyms, rhymes, or stories that can help you remember information. For instance, to remember the colors of the rainbow, you might use the acronym "ROY G. BIV" (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet).

- Visualization: Create mental images that represent what you're trying to remember. The more vivid and unusual the imagery, the more likely it will stick in your memory.

- Associations: Connect the new information to something you already know. For example, if you're learning a new language, you might associate the word for "book" with the image of a book in your house.

- Frequent Review and Application: Spaced repetition, which involves reviewing information at increasing intervals, helps reinforce memory. Also, try to apply the information in practical situations. Using the new knowledge makes it more relevant and easier to remember.

- Organize Information: Break down complex information into smaller, organized chunks or categories. Creating outlines or mind maps can also help you see the relationships between pieces of information.

- Stay Engaged: The more interested and engaged you are with the material, the more likely you'll be to remember it. Try to find aspects of the subject that intrigue you or look for how it's relevant to your goals and wishes.

- Emotional Involvement: Research shows that memory is often linked with emotions. Try to generate emotional responses to the material you want to remember. For instance, if you are moved by a particular scene in a historical documentary, the facts around that event may stick with you longer.

Remember, elaborative rehearsal is more effective when it is an active process. Passive reading or listening is less likely to turn short-term memories into long-term ones. By making the information meaningful and engaging in a deeper way, you strengthen the neural connections that are necessary for transferring and storing information in long-term memory.

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of memory where information is stored indefinitely. Information has to be encoded from STM to LTM, where it can be retrieved much later, even after years.

Example

Learning to drive a car requires processing a tremendous amount of information. Over time, as these skills and knowledge are practiced and repeated, they're encoded into long-term memory, allowing you to drive without consciously thinking about every action.

Characteristics

- Capacity: Practically unlimited. The brain can store a vast number of memories.

- Duration: Potentially permanent. Some memories can last a lifetime.

- Function: It is the storage of information over an extended period. Mechanisms of memory consolidation later transfer memories for long-term storage.

- Encoding: Information can be encoded semantically (based on meaning) or, less commonly, visually or acoustically.

Types

- Explicit Memory (Declarative): Memories we are aware of and can consciously recall.

- Episodic Memory: Personal experiences and events.

- Semantic Memory: Facts and general knowledge.

- Implicit Memory (Non-Declarative): Memories that are not part of our consciousness, generally skills and tasks.

- Procedural Memory: Know-how memory, like riding a bike.

- Emotional Memory: Emotional associations that may not be consciously accessible.

Implications of the Model

Atkinson and Shiffrin's model laid the groundwork for further research into cognitive processes. One key implication is that since memory storage operates in stages, educators and students can use strategies tailored to each stage for better learning outcomes.

Criticisms and Further Developments

Despite its influence, the model is not without its critics. Some argue that the model is too simplistic and linear, failing to account for the complexities of memory. It also does not adequately address the impact of emotion and motivation on memory. Subsequent models, such as Baddeley and Hitch's working memory model, have addressed some of these criticisms by proposing a more dynamic system of short-term memory processing.

Conclusion

While further research has expanded our understanding of memory beyond Atkinson and Shiffrin's model, the Three-Stage Memory Model serves as an important reminder of the essential processes that underlie our ability to store and recall the vast array of information and experiences that make up our lives. Whether considering sensory inputs, short-term tasks, or the rich tapestry of long-term memories, we can appreciate the elegant complexity of the human memory system.