VM vs Docker

TL;DR - Let's not even compare them to virtual machines. Because really they're just a process. They're a process running on your host operating system. in our case - Linux.

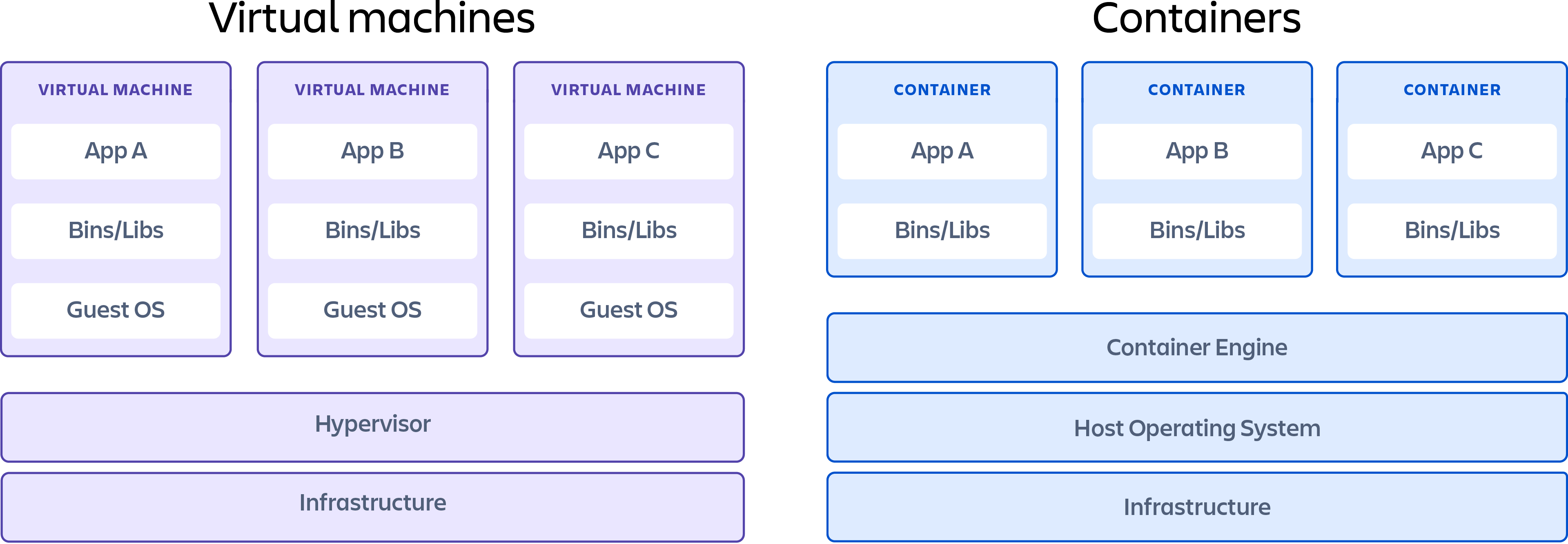

Source: Containers vs. virtual machines

Source: Containers vs. virtual machines

Containers are not VMs

TL;DR - The key differentiator between containers and virtual machines is that virtual machines virtualize an entire machine down to the hardware layers and containers only virtualize software layers above the operating system level.

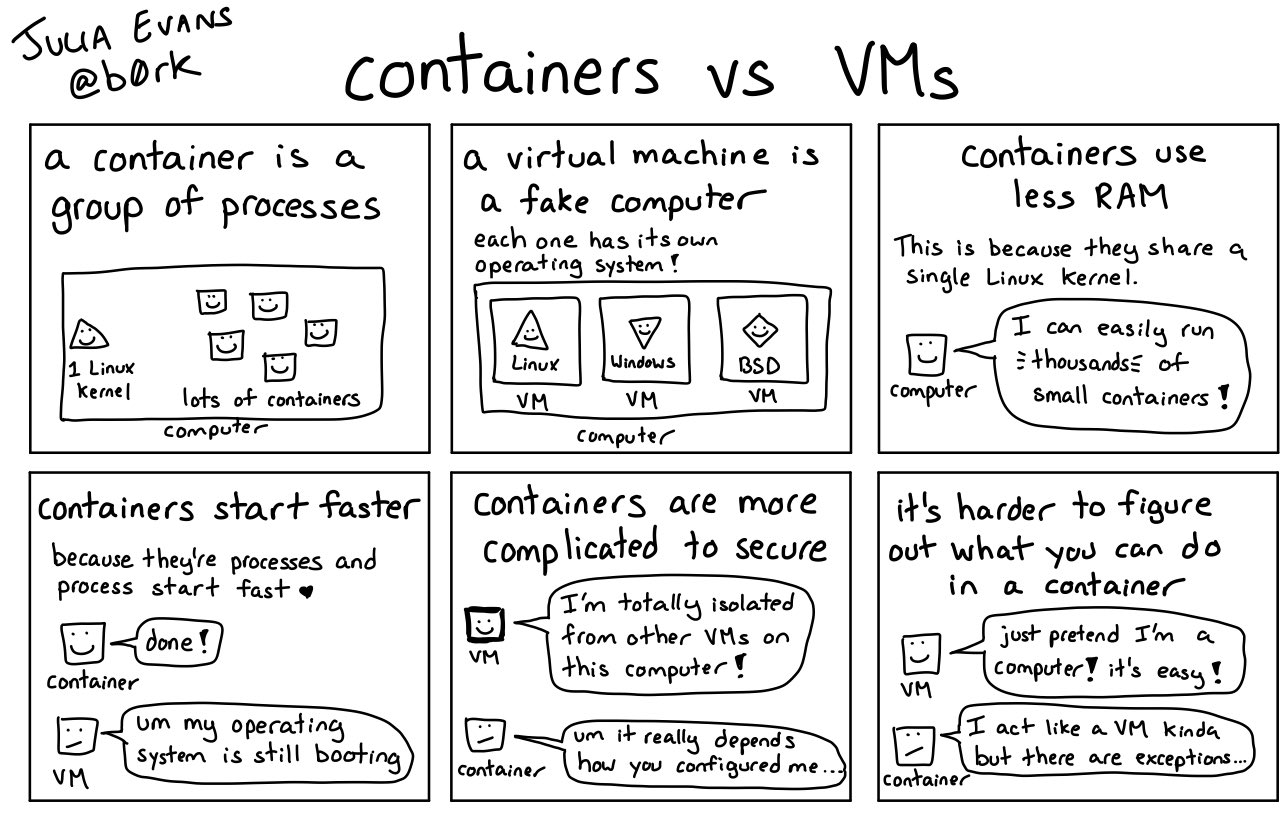

Source: 🔎Julia Evans🔍 - twitter

Source: 🔎Julia Evans🔍 - twitter

A natural response when first working with Docker containers is to try and frame them in terms of virtual machines. Oftentimes we hear people describe Docker containers as “lightweight VMs”.

This is completely understandable, and many people have done the exact same thing when they first started working with Docker. It’s easy to connect those dots as both technologies share some characteristics. Both are designed to provide an isolated environment in which to run an application. Additionally, in both cases that environment is represented as a binary artifact that can be moved between hosts. There may be other similarities, but these are the two biggest.

The key is that the underlying architecture is fundamentally different between the containers and virtual machines. The analogy we use here at Docker is comparing houses (virtual machines) to apartments (Docker containers).

-

Houses (the VMs) are fully self-contained and offer protection from unwanted guests. They also each possess their own infrastructure – plumbing, heating, electrical, etc. Furthermore, in the vast majority of cases houses are all going to have at a minimum a bedroom, living area, bathroom, and kitchen. It’s incredibly difficult to ever find a “studio house” – even if one buys the smallest house they can find, they may end up buying more than they need because that’s just how houses are built.

-

Apartments (Docker containers) also offer protection from unwanted guests, but they are built around shared infrastructure. The apartment building (the server running the Docker daemon, otherwise known as a Docker host) offers shared plumbing, heating, electrical, etc. to each apartment. Additionally apartments are offered in several different sizes – from studio to multi-bedroom penthouse. You’re only renting exactly what you need.

Underlying resources

Docker containers share the underlying resources of the Docker host. Furthermore, developers build a Docker image that includes exactly what they need to run their application: starting with the basics and adding in only what is needed by the application.

Virtual machines are built in the opposite direction. They start with a full operating system and, depending on the application, developers may or may not be able to strip out unwanted components.

Comman confusion

For a lot of people these concepts are easily grasped. However, even when someone understands the architectural differences between Docker containers and virtual machines, they will often still try and adapt their current thoughts and processes around VMs to containers. (We will answer these questions in the next section)

- “How do I backup a container?”

- “What’s my patch management strategy for my running containers?”

- “Where does the application server run?”

To many the light bulb moment comes when they realize that Docker is not a virtualization technology, it’s an application delivery technology.

VM-centered world

In a VM-centered world, the unit of abstraction is a monolithic VM that stores not only application code, but often the stateful data. A VM takes everything that used to sit on a physical server and just packs it into a single binary so it can be moved around. But it is still the same thing.

Docker containers

With Docker containers the abstraction is the application; or more accurately a service that helps to make up the application.

Micro-services architecture,

In a micro-services architecture, many small services (each represented as a single Docker container) comprise an application. Applications are now able to be deconstructed into much smaller components which fundamentally changes the way they are initially developed, and then managed in production.

The answers of above 3 questions

How do I backup a container?

So, how does a sysadmin backup a Docker container? They don’t. The application data doesn’t live in the container, it lives in a Docker volume that is shared between 1-N containers as defined by the application architecture. Sysadmins backup the data volume, and forget about the container. Optimally Docker containers are completely stateless and immutable.

What’s my patch management strategy for my running containers?

Certainly patches will still be part of the sysadmin’s world, but they aren’t applied to running Docker containers. In reality if someone patched a running container, and then spun up new containers based on an unpatched image, serious chaos could ensue. Instead admins update their existing Docker image, stop their running containers, and start up new ones. Because a container can be spun up in a fraction off a second, these updates are done in exponentially more quickly than they are with virtual machines.

Where does the application server run

Application servers translates into a service run inside of a Docker container. Certainly there may be cases where microservices-based applications need to connect to a non-containerized service, but for the most part standalone servers where application code is executed give way to one or more containers that provide the same functionality with much less overhead (and much better horizontal scaling)